Tagged: IMF

The New Politics of Inequality at the World Economic Forum (again)

Christine Lagarde, the IMF and the World Economic Forum

Christine Lagarde has once again used the World Economic Forum meeting in Davos this week to highlight her quest to refocus the International Monetary Fund on the task of reducing inequality. Mme Lagarde has repeatedly made such statements at the WEF and I’ve covered these on this blog before.

Speaking at a Bloomberg sponsored event on the ‘squeezed and angry’ middle classes throughout the world, she reminded the audience that she had warned of the destabilising political effect that inequality might have. With the rise of populist political movements now very much in evidence she was once again making the same warning.

Christine Lagarde Speaking at the World Economic Forum this week

I have previously noted the IMF’s interest in inequality under Lagarde and went to meet some of the people in the Fund responsible for the research published in 2013 and 2014 to ask them about it. I concluded then that the concern was genuine but that this was motivated in the main by a concern to prevent political destabilisation rather than an egalitarian ethical standpoint. To be clear here – this is not a critique of the individuals; they appeared to have a very developed ethical commitment to equality, but an organisational one. It seemed to me then that what had enabled their work on inequality (which had been around for a long time) was the stance of the IMF’s Managing Director (Mme Lagarde and Dominique Strauss-Kahn before her) but also the context of increasing political instability. I called this the ‘New Global Politics of Inequality from above’.

The struggle for reform

This week Lagarde commented on her own struggles to turnaround the IMF to focus on inequality. It is worth reading this at length:

“[back in 2013/14] we were demonstrating that excessive inequalities were putting a brake on sustainable growth… I got a strong backlash from economists in particular saying that it was not really any of their business to worry about these things, including in my own institution, which has now been very much converted to the importance of inequality and studying it and providing policies in response to that… we now have a very opportune time to put in place policies that we know will help…”

So to summarise this and the tenor of the Davos debate:

- Mme Lagarde recognises that inequality is a problem;

- Davos stakeholders and policy makers should worry about this because it is bad for growth and creates political instability;

- she has tried, against resistance, to change the IMF and to lead the G20 with some success, to focus more on putting in place policies to reduce inequality.

For those with an ethical or just pragmatic concern to reduce inequality some important questions arise from this. These are about how much the Davos set (such as international organisations like the IMF, multinationals, the G20, policy makers and leading NGOs) have genuinely taken action to reduce inequality as a result of this kind of analysis.

So, is the IMF really trying to reduce inequality?

I can’t answer for all of these different organisations, but recent research I undertook with Dr Paul White, did focus on the extent to which the IMF has changed. We undertook our analysis in several stages.

First, we looked at high level pronouncements and reports from the Fund on the subject of inequality. Speeches from Lagarde herself and several important research and policy documents do indeed have a strong focus on reducing inequality. They map out both the case for reducing inequality and identify a series of evidence based conclusions about precisely which sorts of policies might increase or reduce inequality in different types of country.

Next, we took that list of policies: that is the policies that the Fund itself says will reduce inequality. Rather than evaluating ourselves whether these policies would reduce inequality, we took that at face value and looked for evidence that these policies were being promoted by the Fund when it works with member states.

Few international organisations have as direct a channel of influence on their member states as the IMF. This comes mainly in two forms. The IMF regularly provides advice and recommendation to all members (nearly all countries in the world). While these recommendations are not mandatory, they do carry some weight because capital markets may view this advice as sensible and therefore access to funding for government programmes may be affected if governments ignore it. For governments who borrow from the Fund, this advice obviously has much stronger leverage; it is often part of the conditions that the Fund attaches to receiving financial support.

The next step was to look at the operational guidance that IMF staff work under when producing advice to member states. We wanted to see the extent to which the policies the Fund says reduce inequality are present in that guidance. There have been several changes to this guidance recently and at a headline level concerns with sustaining growth and reducing inequality appeared to have triggered those changes. Evidence then of Mme Lagarde’s reform programme.

But when we looked at the actual detail of the changes to the operational guidance and the various supporting documents, it was difficult to discern the emphasis on reducing inequality. It seemed that whatever message had come from the top about this, got lost somewhere in the technocratic process of re-drafting the operational guidance.

Finally, we looked at recent IMF documents providing advice to member states. We looked only at recommendations produced after the new operational guidelines were in place. We were specifically looking for recommendations which echoed those in the Fund’s own lists of policies which might reduce inequality. We also searched the documents for any mention of concerns with inequality, income distribution and the like. Perhaps unsurprisingly, we found very little evidence of any of this.

So it seems that while there may be an attempt to reform the IMF to focus on reducing inequality, this has not yet fully percolated through the organisation to operational practice. We shouldn’t necessarily be surprised. Reform takes time after all.

Rhetoric and practice

There are several possible explanations for the lack of change.

Perhaps it is an ‘organised hypocrisy’ or ‘legitimation strategy’: high level pronouncements on socio-economic and gender inequality are a veil for the real business of the Fund, which is unconcerned with these sometimes negative consequences of promoting growth and global market integration.

Alternatively, perhaps it merely represents institutional stickiness: reform takes time and not enough time has passed. If either of these explanations is adequate, research like that undertaken by Paul and I, as well as others (Best, Broome, Kentikelenis et al., Weaver, Gronau and Schmidtke etc) help to keep the pressure on and support the reform efforts of committed leaders like Lagarde.

I am not yet in a position to be definitive on this, but I suspect something of both these explanations, placed in a broader analysis of the role of international organisations in the expanding global economy, is the real answer. But to stand up that conclusion, more research is necessary.

Where to from here?

For me the next phase in my research on the IMF is to continue to audit policy documents to see whether there is any identifiable change in practice. I also intend to enquire with Fund staff, and perhaps Christine Lagarde herself, as to what they think explains the apparent dissonance between high level policy and practice.

Whatever the outcome of this research, it is important that those involved in highlighting the issue of global inequality, continue to keep the pressure on, to hold the powerful to account. That includes the IMF, Mme Lagarde and all those present at the Word Economic Forum this week of course.

The ‘New Politics of Inequality and the EU Referendum’ via a Facebook squabble

Politics through Facebook

This week I was prompted to remember the birthday of one of my oldest school friends by a helpful message from Facebook. I didn’t really need a reminder, but nevertheless I responded to Facebook’s exhortation and dutifully posted the obligatory – if low key – ‘Happy Birthday’ message on his Facebook page.

But I don’t expect a response, and perhaps I don’t deserve one.

On Friday June 24th- – the morning of the EU referendum result – I foolishly entered into a Facebook quarrel with this old friend. He was posting in muted but triumphal terms about the decision to leave the EU, and I objected to some of the explanations used. He obviously received several posts and messages that were negative, and, despite some enthusiastic support from others in his network, he posted on Saturday morning that he didn’t want to offend anyone and would delete the posts in question. I suspecthe thought some people – and I fell into that camp – were sore losers and should ‘just get on with it’, but like his initial post his tone was polite, consensual and intended to pour oil on troubled waters.

So why had his posts motivated me in the first place?

Frankly, the reason was that I recognised his concerns. He explained his antipathy toward the EU as a result of concerns about de-industrialisation, the loss of well paid and secure employment. He was worried about the social implications of this; in terms of increased insecurity and a sense of disruption of the local communities that had relied on these industries. I know from our friendship that he and his family are long-standing members of those communities which they hold dear. His values are of commitment to place and others.

In the wake of the referendum many remainers have poured scorn on leavers, accusing them of being uninformed, motivated by racism, xenophobia and simplistic nationalism. All of these are easy to dismiss as the product of a lack of education or rational thought. But my friend’s posts did not fall into any of these categories. He was thoughtful, well informed and motivated by a commendable and deeply held commitment to community and place, and concerns over the insecurity of both.

What is also notable about this friend is that he has been successful in adjusting to the changes he bemoans. He is well trained and qualified, and I assume reasonably well paid in a high skilled job. His concerns are about material changes in the communities he values, but they are not sour grapes from a loser in the globalisation story. He was expressing concerns about the wider and common effects of global economic changes, of which European integration was just one part.

I clearly should have been more cautious with my response to my old friend, and hopefully in time our spat will be forgotten. The irony is of course that his concerns very much feature in my own research.

That same weekend similar – albeit more consensual – discussions between myself and a range of academic colleagues, also facilitated by Facebook, suggested a more hopeful trajectory. The Facebook ‘echo chamber generated’ new friends too – all motivated by the EU result and concerned about the need to do more to engage with the political concerns that motivated my friend.

That same weekend similar – albeit more consensual – discussions between myself and a range of academic colleagues, also facilitated by Facebook, suggested a more hopeful trajectory. The Facebook ‘echo chamber generated’ new friends too – all motivated by the EU result and concerned about the need to do more to engage with the political concerns that motivated my friend.

We all recognised that we have been too insular, too concerned with metrics of student satisfaction, research impact and academic reputation to spend sufficient time on the politics of the real world. As the algorithms of social media generated a discussion of increasing numbers of like minded colleagues, more than 250 of us joined a discussion. The result was that we rather quickly formed a new think tank – InformED. I hope that in the months and years to come you will hear more about our work, for that will suggest that we have carried through our commitment to reach out beyond the confines of the University lecture hall and academic conference room.

So aside from introducing InformED, it is the links between the EU referendum result and my research on ‘the New Politics of Inequality’ that I want to tease out in this (admittedly over-long) post. I have two core arguments.

The first is that the pressure for the referendum and the result were partly generated by a ‘New Politics of Inequality’.

The second is that if we are to leave the EU, then it is vitally important that this process is undertaken in a way that involves us all taking greater political responsibility. For their part, politicians need to take responsibility for the social divisions they have created. Critical academics like me and my colleagues in InformED, have a responsibility to reach out beyond the academy to influence this, and the wider public have a responsibility to engage with political debate in a more substantive way.

The New Politics of Inequality From Below

In a paper, currently under review and co-authored with Daniela Tepe-Belfrage, we argue that levels of inequality in the UK are fracturing the political consensus that had been reflected in the post-war middle class. In a paper published in 2014 I argued that during the 1980s, Thatrcherism had sought to separate out different sections of the working class, seeking to differentiate between a deserving skilled working class able to cope with increased competitiveness and those less able to cope. This has been a long-running trend; the current government has repeatedly sought to emphasise its support for ‘hard working families’ against the ‘undeserving poor’.

The argument made by Daniela and I is that the specific forms taken by socio-economic inequality in the UK are now undermining both one and two nation attempts to build political compromises. The much vaunted ‘new middle class’ of the 1960s and 70s sociology text-books is fracturing.

For one thing, the long-term prospects of this group now look less secure. As I argued in my inaugural lecture, the generation now in their twenties and teens look like they will be the first to be considerably worse off than their parents. The exception to this is where families have acquired housing assets to pass between generations sufficient to protect those now in their teens and twenties from increased insecurity. In buy-to-let mortgages at one end of the spectrum and increased private renting at the other, the housing and credit markets are acting as a significant mechanism of upward redistribution.

For another thing, those families affected by these changes increasingly recognise their own declining security. As the recent data from the British Social Attitudes survey shows, concern with inequality is increasing, as it has done for some time.

It is this recognition that has fueled the emerging realignment of British electoral politics. Just before the last general election the British Social Attitudes Survey showed that UKIP voters were just as likely to be concerned about inequality as were labour voters. While some groups mix these concerns with more cosmopolitan cultural politics, others express them through more conservative cultural views. The former group might be more likely to be young, urban and highly educated (or just living in Scotland!); the latter more likely to be out of the major urban centres, older and less well qualified. Without over simplifying things, the former group may be more likely to be among the ‘Momentum’ group supporting a new extra-party popular mobilisation behind Jeremy Corbyn. The latter group are more likely among the ranks of labour and conservative supporters who have switched to UKIP in recent years.

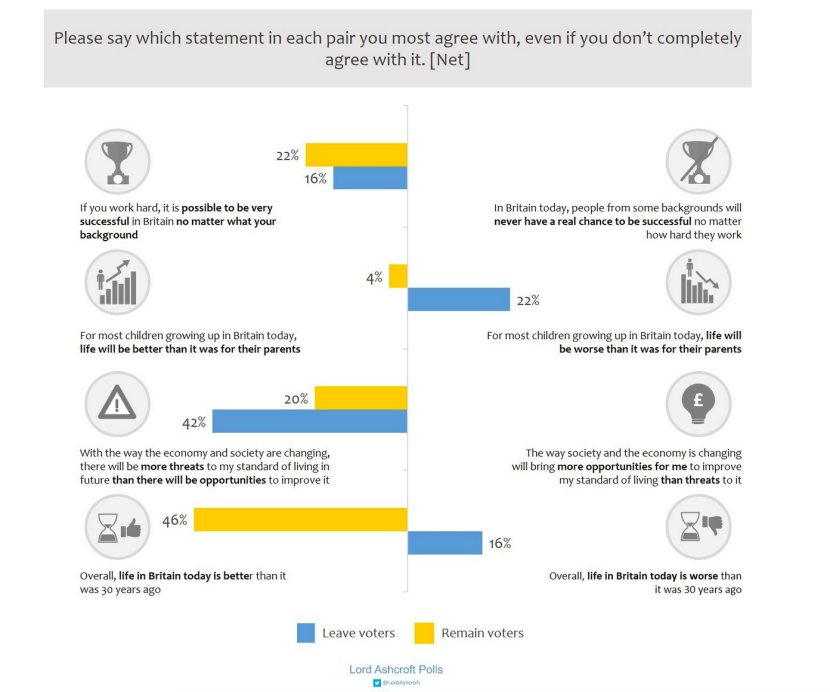

Ashcroft Poll data shows common concerns about insecurity among remainers and leavers. Click on the image to goto the Ashcroft Poll site.

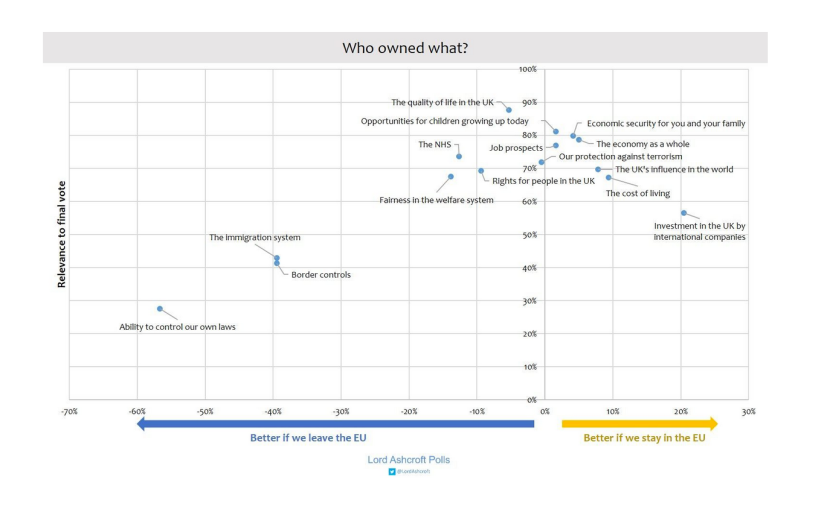

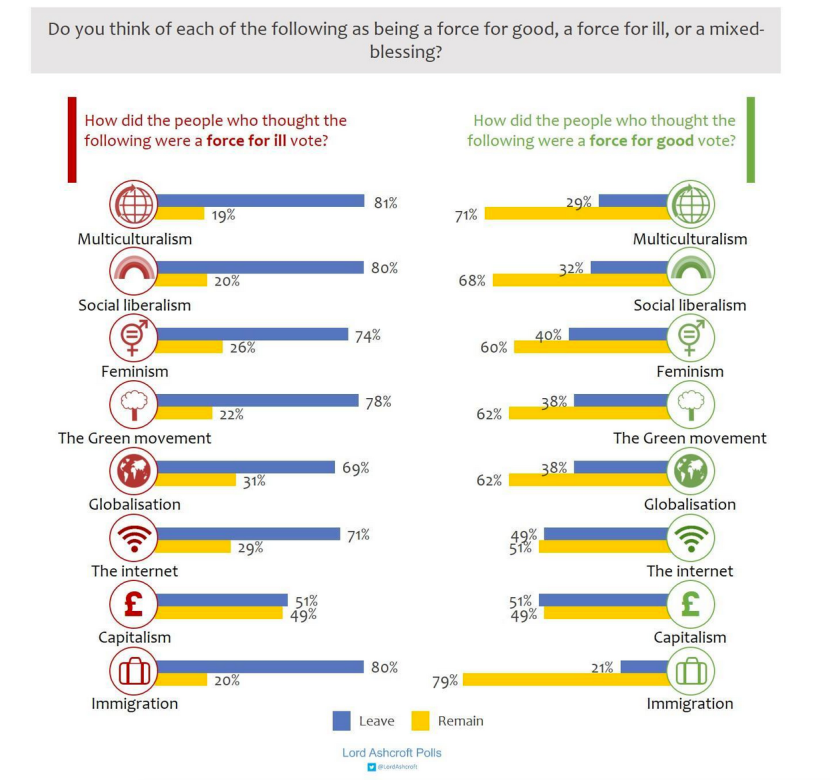

As the Ashcroft polls show, these shared concerns and divergent interpretations of them were neatly aligned with the propensity to vote remain or leave in the EU referendum. Leave voters were more likely to be socially and culturally conservative while remainers were more likely to be socially and culturally cosmopolitan and outward looking (see graphics below). But both groups (see graphic above) were influenced in their decisions by concerns about economic insecurities and the effects of these on social and community stability.

Ashcroft polling data showing the social and cultural values of remainers versus leavers. Click on the images to goto the Ashcroft site for more data.

These patterns are not just present in the UK, they are echoed across Europe and North America. In the US presidential elections similar patterns of support can be seen for Bernie Sanders versus Donald Trump. The Five Star movement in Italy, the formation of Syriza in Greece exemplify the leftward reaction. On the other hand the rise of the far right parties in France, Austria, Denmark and the Netherlands and the Pegida movement in Germany demonstrate the counter trend to view polarisation and insecurity through the prism of cultural stasis and fear of the other. Perhaps more significantly the New Politics of Inequality is also manifest outside of electoral politics in the expressions of protest such as Occupy or the Indignados in Spain, or the rise of far right protest movements all across Europe. Evidence can be found also in declining popular confidence in political institutions.

The New Politics of Inequality then are fracturing the post-war consensus in the highly developed nations of the North America and Europe, from both left and right. Inequality and cultural change are popularly viewed negatively on both ends of the political spectrum.

The fracturing of the new middle class is perhaps realising Marx’s prophecy that the class structure would evolve into two great and opposing classes. The sloganeering of the 1% versus the 99% seem to suggest that. However, it seems that the 99% are definitely not drawn together in a cohesive class consciousness by their common economic realities, but are fractured both within and across countries on their cultural response to those economic realities.

The EU referendum result represents the most significant real world expression of this so far in terms of UK, European and even global politics, though the US election result may clearly trump(!) it.

The New Politics of Inequality from Above

Several of the other papers I have written recently have addressed what might be called here the ‘New Politics of Inequality from Above’. Here I refer to the elite concern about levels of inequality being politically, economically and socially destabilising. This concern has been emergent over the last decade, but is particularly pronounced since the great financial crisis of 2008.

Evidence of this concern can be drawn from the policy documents of significant international organisations such as the International Monetary Fund, the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development, World Bank and the World Economic Forum. These organisations have different roles and functions, but collectively one of the things they do is act as the think tanks and ideas forums of elite policy knowledge. Social, economic and political changes are interpreted by these organisations as particular problems for the status quo. The OECD began to worry about inequality first, but all of them have published high level papers rendering inequality as a policy problem over the last five years, as I discuss in a paper published in Spectrum late last year.

Of interest here is that the European Commission definitely qualifies as one of those transnational organisations that has had influence in shaping the elite interpretation of ‘problems’ that national governments choose to focus on and frame particular responses to these in terms of recommended – and in the case of the Commission sometimes mandated – policies. It is also the case that inequality has featured on the list of concerns the Commission has raised over the last five years.

The key terms of this new politics of inequality from above are that inequality is not rendered by these elite think tanks as an ethical problem. This new politics does not represent a ‘road to Damascus’ moment for these organisations. Rather they are concerned precisely because inequality might now be seen as a ‘risk’ to the stability of globalisation. As such they are busy trying to persuade national governments to take these risks seriously.

This new politics of inequality from above was clearly apparent in the EU referendum process. For years policy elites have sought to exploit social differences to manage the process of disciplining their populations to accept lower wages, and in some cases lower standards of living also. This has been possible politically, precisely because elites have mobilised fear and sometimes nationalism to generate this division. Politicians have regularly sought to use the image of the immigrant, the welfare or health tourist or the domestic welfare benefit recipient as a negative foil for generating support among the rest of the population.

However, that fear and xenophobia is now rather like the ‘Sorcerers Apprentice’; its animated spirit has got out of hand is undermining the position of established elites. Specifically in the UK, both Labour and Conservative Parties have played the ‘immigration’ and ‘race’ cards, exploiting fears over insecurities to court popular appeal.

Indeed, the now defining moment of Gordon Brown’s tenure as Prime Minister might be thought of as the moment that he unguardedly let slip his discomfort with that narrative when commenting that he thought remarks made to him by a Labour party supporter about migration were bigotry.

Of course when he realised (see the image above from the Telegraph website capturing the moment) he had been recorded making these comments he immediately back-tracked and offered profuse apologies for ever even thinking about challenging fear expressed as xenophobia. The episode is still referred to as evidence that Brown was out of touch with popular opinion, and – no doubt encouraged by the party machine – he certainly did not try to challenge this populism. It was an episode that demonstrates the cultural divergence in responses to inequality, its manipulation by politicians and the way that this is now hard to control.

But in the run up to the referendum vote, elite concern seemed ever more shrill in the face of the evidence that the Sorcerer’s broom might now be beginning to act on its own motivation, and out of their control. As the campaign progressed and opinion polls showed a close contest, the array of large businesses and elite policy think tanks became increasingly willing to enter the fray. The supposedly neutral civil service machine also strained at the leash to get involved to put public opinion back in its place, as both the Treasury and Bank of England – the oldest and most central institutional structures of the UK state – sought to raise their own fears of what a Brexit vote would mean to the elite transnational status quo.

The elites were trembling, and, as it turned out, they had good cause. The sight of Bank of England governer Mark Carney standing in Threadneedle Street promising that the Bank would step-in to rescue the financial markets, and stablise the global financial system, was evidence of how seriously those elites were rocked. That other Central Banks immediately joined forces to make the same promises is only evidence of the transnational nature of those elites.

Why has inequality risen?

Again, I and many others have addressed the underlying reasons for rising inequality in a number of places, such as my talk in launching the Global Inequalities research cluster at Leeds Beckett, and in a workshop paper to an ESRC seminar at Goldsmiths University late last year. There is also no shortage of explanations. Again, the OECD, the IMF et al. have all jumped on the bandwagon of explaining rising inequality.

The most remarkable thing in terms of the New Politics of Inequality is that the explanations put forward by these elite organisations now are remarkably similar to those put forward for a long time by critical scholars in international political economy and the wider social sciences. Ofcourse the different proponents of these explanations place varying degrees of emphasis on different parts of the explanation, and often use different language to describe them. Semantics aside the more or less accepted basket of factors that have increased inequality include:

- Increasing competition resulting from increased openness to trade and, in some circumstances, increased migration, also. Migration though tends only to have shorter-term and more localised effects and it should be remembered that the migrants themselves are the subject to the negative effects of this competition.

- Offshoring and globalization as some industries and occupations have moved overseas.

- Skill Biased Technological change – resulting from the substitution of machines and computers for labour, meaning some occupational roles have disappeared while other more skilled jobs have attracted higher wages.

- Privatisation of state owned enterprises, which has invariably put a downward pressure on wages in public sector employment, often more dominated by women.

- The decline of trade union membership and collective bargaining.

- Labour market policy, including anti-trade union legislation and reduced employment protection legislation.

Of course where critical scholars and the elite international organisations part company is that these are the very changes long-recommended by the OECD, IMF etc. And in the face of rising inequality and social destabilization they still recommend that the answer is more competitiveness. But, as Paul Cammack has long argued, pursuing competitiveness as a solution to the problem of increased competition is a fairly circular argument. Its hard to find a different path out of a tricky situation if one is going in circles!

The European Union and the New Politics of Inequality

European integration was very much the product of the post-war international compromise; motivated by geo-political desires to tie the countries of Europe together in a peaceful free-trade zone of collaboration, while bolstering them against the threat of Soviet expansion. These geo-political concerns suppressed and held in check the tension between two important component elements of EU integration. These were first a political and social liberal project to spread and realise the individual rights of citizens through constitutionalism ;and second an economic liberal project to promote market integration.

After the end of the Cold War the geo-political suppression of tensions between these two projects was removed, and the market liberal project began to emerge as dominant.

As Paul Beeckmans and I argued in a recent paper, the process of economic meta-governance in EU integration has increasingly pursued the objective of economic competitiveness to the detriment of concerns to build a ‘Social Europe’. The suppression of wages and living standards has been encouraged by the European Commission as an element of EU integration to meet these ends. If in any doubt about this, just ask the Greek population that has been at the harshest end of this discipline over the last 6 years.

In sum, EU integration has increasingly taken on the concern with competitiveness that has generated the inequality underpinning the damaging ‘new politics’ I describe above. So, if I am so critical about EU integration as was my friend and the wider ‘Lexiteer’ (Left wing leave voters) campaign right about the need for the UK to leave the EU?

My answer would be ‘no’, on several grounds.

First, while the EU – and the European Council and European Commission in particular, have worked to promote competitiveness at the cost of greater inequality and social tensions, they did not really have this impact in the UK. That is principally because the UK government (under all political parties) has always run ahead of the EU in these objectives.

Indeed, many other Member States have often complained about the role of the UK in encouraging market-oriented reform in the wider EU. While European integration has been consistent with the types of reform that have realised the New Politics of Inequality in the UK, it has not been a cause of it and at times has acted as a substantial drag on UK ambitions. Constant debates over the implementation of EU directives strengthening workers rights are prime evidence of this, with the UK often being oppositional in the European discussion on these matters and sluggish to implement the resulting watered down versions that could be agreed in the face of UK objections.

Second, the majority opinion among the political elite (among remainers and leavers alike) is that leaving the EU should be complemented by immediately rejoining the single market or negotiating other equivalent trade deals. Leaving aside the difficulty of this, as pointed out by Gabriel Siles-Brugge, the direct implication is that leaving will see more market oriented reform and a greater dominance of the economic liberal project over the political liberal one. Put simply, as Ruth Cain also persuasively argues it will accentuate the conditions which generated the New Politics of Inequality in the first place.

Third, the subordinated aspect of EU integration – shared citizenship, a European identity, the idea of peace and cooperation between nations, cosmopolitan values of tolerance and openness, individual rights and Europe’s great gift to the world: the idea that we collectively have a social and economic responsibility to one another, as expressed through the institutions of a welfare state and social protection – may all be on the back foot, but they are not gone. We should be promoting a radically different Europe that defends and promotes these values, not turning our back on it.

Where to now?

Plenty of commentators have spent the last week worrying about the precise ways in which the fallout from Brexit will play out in terms of the potential for a second referendum, Scottish cessation from the Union and the politics of Party leadership. The blogosphere is alight with this stuff and it is all many of my colleagues, friends and acquaintances have been able to talk about since July 25th. It is not just ‘lefty academics’ either. I have overheard conversations in shops, on public transport and in pubs that all suggest a very much heightened interest in politics and a dawning realisation of the dynamics I describe above. These things are clearly significant and comment worthy in themselves.

However, the big story here is not so much the contingent terms in which the immediate processes of responding to the vote pan out. Rather, it is in the underlying socio-economic trends and their rival interpretations in cultural politics. The apparent rise of racial harassment and violence is one immediate expression of this, but so too is the widespread antagonism between the two sides of the debate. My Facebook spat is clearly part of this!

In the fallout then there is increased responsibility on all sides.

Politicians have a clear responsibility to engage with the problems in place of Westminster games.

Academics, such as those coming together in this new think tank, have a duty to do more to engage with public opinion and inform scrutiny of politicians. Critical academics working in the fields of international political economy, sociology, social policy, European studies and critical management studies have long been aware of rising inequality and its consequences in the form of alienation and disenfranchisement. It is crucial that those critical analyses find their way from the lecture hall and conference room to the public debate. We need to do more to engage the public directly and to influence the political debate in the media. This is the objective of my colleagues who have come together to create InformED.

The public also have an obligation here. The stories over the last week or so about Brexit voters immediately becoming ‘regrexiteers’ when the implications of their actions became clear and about the prominence of ‘What is the EU?’ searches on Google suggest a democratic obligation to be better informed before contributing to collective decisions. They also suggest an increased realisation of this.

Acting on these responsibilities is no ‘academic’ issue. It is of vital importance if we are not to travel further down the road of cultural divisions. As a divided nation we are easier to rule in the interests of the few and not the many. Divergent cultural political reactions to common insecurities risk the many blaming each other for our common inequalities, and letting the few of the hook.

Moreover, these circumstances – common insecurities, fear of the future, disenchantment with existing institutions – look much like the political conditions that led to the downward spiral into the Second World War. I don’t say we are anywhere near that now, but we are closer now than we were, and the warning signs are clearly there. It is imperative that we all act now to ensure that we do not travel any further down that path.

The New Politics of Inequality

This short paper is a summary of my inaugural lecture, given on April 29th 2015. A longer version of the lecture notes are available here, and a video of the lecture will be available in the near future.

In some ways those of us who have long worried about rising inequality ought to be cheered by the prominence now being given to the subject in popular debate. After several decades in which socio-economic inequality was firmly off the agenda, reduced to the discussion only of equal opportunities, inequality is now firmly back on the political agenda. Academic and popular texts, campaigning organisations and powerful international institutions all draw attention to the disproportionate economic and political resources accruing to the ‘1%’ made famous in the sloganeering of the Occupy movement. But I argue in this lecture that this New Politics of Inequality might not be quite so progressive as it at first appears.

My argument is that the New Politics of Inequality is mainly concerned to contain the negative affects of inequality in terms of social and political stability, rather than an ethical commitment to egalitarianism. This is the case whether it is found in Thomas Piketty’s high profile Capital in the Twenty First Century or OECD and IMF reports (see here for a critique of the New Global Politics of Inequality).

Rising inequality is a common international trend internationally: many countries have experienced increasing inequalities over the last thirty years. Oxfam’s Even it Up campaign has drawn much attention to this. Elsewhere I argue that this is driven by increasing world market integration, resulting in increasing competition between emerging markets and existing ‘advanced’ economies like ours. However, it is also important to examine the specific conditions that pertain inside particular countries; while many countries have witnessed increases in inequality, they are by no means all the same. For this reason, in the lecture I go on to explore some specific aspects of increasing inequality in the UK.

Inequality has been rising in the UK for some time. It rose dramatically in the 1980s, stalled in the 1990s before rising again just before the great recession. Since then, some people draw attention to the fact that headline measures show that inequality declined after 2008. I argue that this is misleading and that data lag and measurement issues are hiding the true situation. Reductions in welfare generosity after 2012, changes in employment conditions and earnings since 2008 and the recovery of asset values owned largely by better off households in the last two years will mean that over the short-term we can expect to see headline inequality rise again to at least pre-crisis levels.

Source: IFS Incomes Data, derived from the Households Below Average Income, Family Expenditure Survey and Family Resources Survey. See: http://www.ifs.org.uk/fiscalFacts/povertyStats, accessed 2-04-15.

In this sense, the effect of the crisis has been to reinforce existing inequalities rather than reduce them. Earnings have fallen disproportionately at the bottom of the income distribution than at the top, full time earnings have declined more for women more than for men, and the household incomes of ethnic minority groups have for the most part fallen by more than for white households. Ethnic minority households also remain more likely to experience poverty and have even larger income differentials than do white households. But perhaps the biggest shift experienced in the crisis has been the structural decline in the position of young people in terms of employment, earnings and wealth accumulation. Given what we know about the prospects for young people who enter the labour market during a recession, we can expect that these disadvantages will continue through their life-course.

It is the experience of these younger groups that I argue will drive a longer-term structural pressure toward greater inequality, similar to that which Piketty identifies. First, the data shows that younger age groups experience greater income inequality than do older cohorts. Second, over and above their labour market disadvantage in terms of employment and earnings, those who entered the labour market during the crisis are much less likely to own their own home than were those who entered the labour market before the crisis. Just short of 50% of those below 35 are living in private rented accommodation. They are not benefiting from the falling mortgage costs associated with homeowners. Third, because of the unequal accrual of housing, financial and pension assets in their parents’ generation some will be better protected by inheritance than others.

Of course these are long-term pressures and much can happen to contain and offset them, before they are fully realised. This is though the problem associated with the New Politics of Inequality: polarisation within the ‘new middle classes’. It is this structural pressure toward polarisation, rather than just the experiences and disproportionate influence of the ‘1%’ that I will be discussing in the lecture. One possible outcome of this inter-generational polarisation is increasing political and social destabilisation and of course it is this destabilisation that I claim the New Politics of Inequality is most concerned to avoid.

So what evidence is there of the New Politics of Inequality in UK domestic politics?

The language of the two main parties as they seek to differentiate between a deserving and undeserving poor or to protect a ‘squeezed middle’ from the cost of living crisis is certainly evidence of a recognition of the way that inequality is experienced in ‘everyday life’.

The shifting electoral landscape and the emergence of smaller parties is also partly reflective of this. The SNP may have lost the referendum in which they made inequality a major feature, but the medium term impact of that campaign may be to make them ‘king makers’ in a hung Westminster parliament. UKIP may to some extent look like a two issue (Europe and immigration) party, but its supporters are both socially conservative and very concerned about inequality. The Green Party has made inequality a key issue alongside environmental sustainability. So to that extent, inequality is emergent as a key political issue in electoral as well as protest politics.

This is the agenda for my research over the next few years. In a range of projects with colleagues in our Global Inequalities research programme at Leeds Beckett University and collaborators at other Universities in the UK and beyond, I will focus on:

- The way in which household and community structures interact with public services, housing and labour markets to produce and reproduce inequality over time. This research is being undertaken as part of a large international collaboration.

- The extent to which the New Politics of Inequality is sustained over time and whether it represents a real and substantive concern to limit or even reduce inequality in order to contain destabilisation. An alternative is that the New Politics of Inequality becomes merely an attempt at discursive legitimation of the status quo.

IMF tells UK to ease up on austerity – I told you so

See http://www.guardian.co.uk/politics/2013/apr/18/george-osborne-imf-austerity

Christine Lagarde, Head of the IMF, has issued a not-so-coded warning to George Osborne that his austerity policies are damaging the UK economy and reducing growth prospects. Given the discussion I had with a bunch of final year Undergraduates yesterday, in our class on global economic governance, I thought a few comments were worthwhile.

First, in my mission to improve understanding about the way international organisations work, among their many student critics, I was making the point that the IMF is not so omnipotent as critical students often think. It can’t do that much to force a government down a particular path, unless that is the government in question wants cash, and even then the IMF has frequently been frustrated at the ‘fungibility’ (I’ll explain below) of the promises that they secure. In this instance, as Larry Elliott notes, the UK is not in balance of payments trouble, does not need IMF support, and therefore can just ignore the advice offered when IMF officials visit in the near future to view the British economy, as the charter of the IMF mandates. This is different to the case that I talked about in class yesterday of 1976 when the Labour government of the time began the work of Thatcherism before Thatcher (if Thatcherism is to be ‘credited’ as it has been this week, then let’s get it straight – she was opportunist rather than ‘towering’ – but another post is on its way about that). Back then some argued that the UK did need IMF support (not all – see Tony Benn on that) and in response for that help the IMF encouraged the UK government to begin its neo-liberal revolution.

But even when the IMF provides assistance, it doesn’t always get what it wants. There has been much gnashing of teeth in the past because governments in the developing world haven’t always done what they promised to do in return for IMF support. This is the fungibility I referred to above. Alongside vociferous protests from left-wing activists that conditionality was essentially imperialistic, this what was behind the much trumpeted decision in the early 2000s to end conditionality and replace it with ‘selectivity’. This is the policy of only providing support in ‘tranches’ and after governments have already demonstrated their commitment to the recommended reform agenda. For those Global Governance students still reading (!) this occurred alongside the shift to what we now call the ‘Post-Washington Consensus’ and will be the subject of next week’s class.

There was a third point I wanted to make about this news and that relates to advisability of austerity policies themselves. After discussions with some good friends (Greig Charnock, Stuart Shields, Hugo Radice, Werner Bonefield, Huw Mcartney, Hilary Wainwright among them) at meeting of the Transpennine Group in 2010 I drafted a piece for Red Pepper that summarised some of our concerns about the way in which austerity was being justified and the substance of the plans themselves. We warned that the case for austerity relied on highly questionable propositions and ran the real danger of choking off growth. Lagarde and the IMF seem to be suggesting that we were right. To read what we said in 2010:

click here for the Red Pepper article

and